A "perfect" test to predict (bad) outcomes after cardiac arrest?

Finally, specific guidance that could help in the toughest of clinical situations

When a person survives a cardiac arrest but doesn’t wake up for days, families need to make wrenching decisions to either continue or withdraw life-sustaining therapies.

They need and deserve clear, accurate guidance from their physicians and health care teams as to the likelihood of their loved one recovering neurologic function to a degree they would consider livable.

Unfortunately, clarity and accuracy are rarely possible except in the most clear-cut cases. Even after using all available modalities (exam, imaging, and labs), significant uncertainty usually remains.

Prospective trials for neuroprognostication after cardiac arrest have been plagued by self-fulfilling prophecy bias: when families withdraw care, those patients are counted as deaths, skewing the results toward the negative. Or their data is removed from the analysis entirely, which introduces large unmeasurable biases (as their eventual outcomes could have gone either way).

In the U.S., end-of-life care (and health care generally) is a value-laden and politically sensitive issue. Lacking strong, clear evidence, U.S. professional societies have avoided language that could be seen as encouraging any limitation on care.

The inherent uncertainty and an absence of directive guidelines have left cardiac arrest patients, their families, and the teams that care for them on their own to muddle through the painful and confusing process.

Fortunately, in its latest guideline update, Europe’s major critical care society (ESICM) has moved things a step forward by synthesizing the available data—imperfect though it may be—to provide specific neuroprognostic guidance that has been both lacking and sorely needed.

A Validated Algorithm for Neuroprognostication After Cardiac Arrest

The ESICM framework generally resembles the other major societies’ prognostic guidelines, but goes further by providing actionable data from its model’s validation in multiple patient cohorts.

1. Eliminate confounders.

The first mistake to avoid is making predictions too early. Many patients have improvement of their neurologic exam in the days following cardiac arrest, and many more have confounding factors that must be mitigated before an accurate prediction can be made.

Three days (72 hours) is the absolute minimum, but for many patients, prognostication should be delayed for five days or longer, until all potential other contributors to encephalopathy have been ruled out to the maximal degree feasible:

Hypothermia/targeted temperature management, which should delay prognostication by at least 1-2 days, or about 72 hours after normothermia is achieved;

Sedation and analgesia, whose metabolites commonly take days to clear completely, especially if infusions were provided;

Neuromuscular blockade, whose effects may persist for days if repeated doses or infusions are given during iatrogenic hypothermia;

Toxic-metabolic encephalopathy from sepsis, metabolic derangements, hypoglycemia, etc.

Significant acidemia or alkalemia

Severe hypotension/shock

2. Look for unfavorable signs.

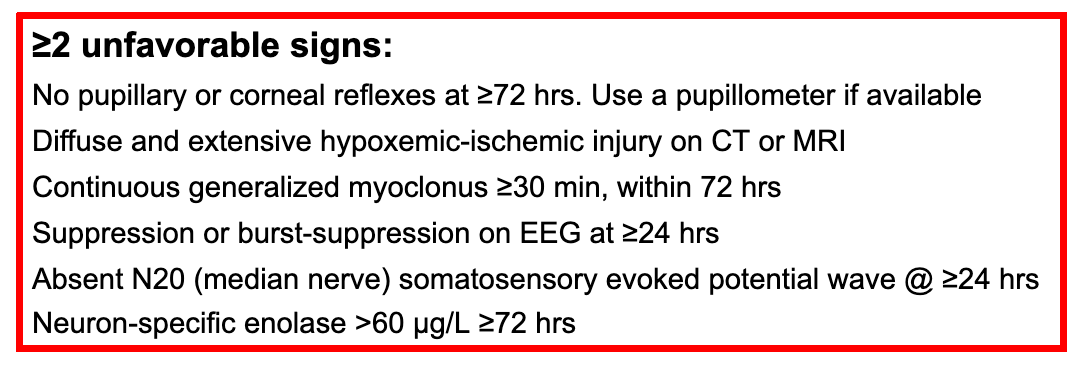

Once enough time and care have occurred to effectively rule out other causes of encephalopathy, if a patient remains unconscious, not following commands, and has any two of the following unfavorable signs, he or she has a predicted 100% chance of a poor neurologic recovery, defined as CPC 3-5 (severe disability or worse) after six months.

3. If 0-1 unfavorable signs are present, look for favorable signs.

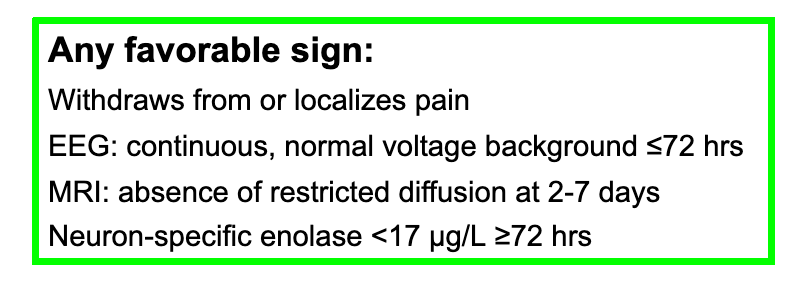

If (and only if) fewer than two unfavorable signs are present, and a patient has at least one of the following favorable signs, there is a higher chance of a positive neurological outcome in six months:

If no unfavorable signs are present and one or more favorable signs are present, the chances of good neurological recovery may increase to 60% or higher with more favorable signs.

4. If <2 unfavorable and no favorable signs, watch and wait.

A large proportion of patients (~45%) will not meet either the “red” or the “green” criteria. Their neurologic prognosis is indeterminate, and accurate predictions cannot be made immediately. Most will continue to have low neurologic function (CPC 3-5), however.

In most studies, awakening occurred within four weeks in patients who regained consciousness. Rare exceptions of later awakening have occurred.

How Reliable Is This Method?

Validation of poor-outcome prediction:

The poor-outcome portion of the ESICM algorithm has been validated in three observational studies (one prospective, two retrospective, totalling 1,791 patients). In these cohorts, the presence of two unfavorable signs predicted a neurologic outcome of CPC 3-5 with no false positives:

660 patients in a registry in South Korea, where withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies is virtually never performed (0.9% in the entire registry), Youn et al Crit Care 2022

794 patients retrospectively at four ICUs in Skane, Sweden, Arctaedius et al Crit Care Med 2024

337 patients prospectively followed at 28 ICUs in France, Bougouin et al Resuscitation 2024

Because the two cohorts outside Korea included a significant portion of withdrawal of life support, “zero false positives” cannot be taken to mean “guaranteed 100% specific.”

Good outcome prediction is extrapolated and not well validated.

The good-outcome portion of the algorithm was added after it was observed that among the ~50% of post-arrest patients with an indeterminate outcome (i.e., those with no unfavorable signs or one), about 20% went on to recover a good CPC status of 1 or 2.

Based on systematic reviews and the combined analyses of ESICM and ILCOR, the favorable signs listed above were confirmed to sometimes predict good outcomes.

However, the favorable signs have not been well validated and don’t predict a good outcome consistently.

For example, in one cohort, one unfavorable plus one favorable sign predicted good neurological recovery in 11% of patients, compared to 3% among those with one unfavorable and no favorable sign.

But in another, 32% of patients with the same combination (one unfavorable + one favorable sign) had a good neurological outcome.

The Problem With CPC 3

People with severe disability (CPC 3) comprise a heterogeneous group. Some can walk, feed themselves, and communicate, but (by definition) they are cognitively impaired enough that they require supervision and are dependent on others. They may live in nursing homes and interact with their families on visits.

This is a far cry from “being a vegetable” or “being kept alive on machines,” the nightmare scenarios families tend to voice and wish to avoid.

There are many debates to be had around counseling and decision-making in anoxic encephalopathy, but this may be the most fundamental. If one considers CPC 3 a life potentially worth living, then the predictive power of the ESICM model (and any that classifies CPC 3 as “bad”) falls apart.

Multimodality is the Future

The ESICM neuroprognostication model confirms the potential for multimodal testing to improve the accuracy of outcome predictions after cardiac arrest.

Each patient and family’s situation is unique and must be treated individually. But as this promising predictive model undergoes further validation, it could help clinicians provide families going through the worst time of their lives with the clearest, most evidence-based guidance possible. It’s been a long time coming.

Once again, and I am not sure that this is malicious, what is missing are the goals of care of the patient. If someone does not want to live a severely disabled life, should we really subject them to that kind of existence? We are not saying actively hasten their death. We are saying allowing them to live and die on their own terms.