NSCLC: Anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy breaks ground, buys time for some

Immunotherapy -- creating antibodies to tumor markers, then activating the immune system to selectively kill cancer cells -- is the newest and most-hyped frontier of oncology. And with some justification: the mechanism is cleaner and kinder than chemotherapy, and being a whole new treatment modality, can complement and augment traditional therapies.

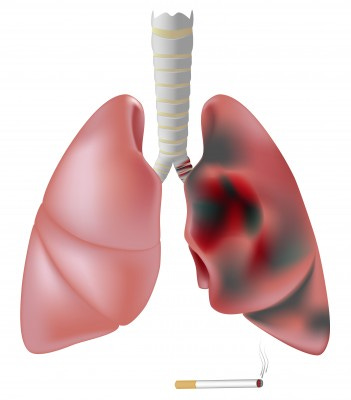

Results of immunotherapy in metastatic melanoma have been encouraging. However, advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been stubbornly impervious to any immunotherapy tested to date.

Now, in the June 28 New England Journal of Medicine, Julie Brahmer, Scott Tykodi, Jon Wigginton et al report that in a small minority of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer, a new immunotherapy called anti-PD-L1 induced radiographic remissions and probably increased real survival.

What They Did

The mechanism goes like this: PD-1 is a protein on T cells that when bound, inhibits the T-cell from killing its targets. Successful cancer cells overexpress PD-L1, the main ligand of PD-1, thus thwarting their death at the hands of T-cells. BMS-936559 is an IgG monoclonal antibody to PD-L1 by Bristol Myers Squibb; when it binds PD-L1, the tumor cells are unprotected and T-cells recognize and kill them.

In a phase I clinical trial, authors gave BMS-936559 to 207 patients every 6 weeks, repeating up to 16 cycles if they tolerated it. Most patients had non small cell lung cancer (75) and melanoma (55). All had either stage IV (metastatic) cancer, or stage III that had progressed despite chemotherapy; most 90% had received previous chemotherapy.

What They Found

Of the 75 patients with advanced NSCLC:

Five had an "objective response," defined as shrinkage of tumor to at least 50% of its previous size. Four of these five had nonsquamous subtypes of NSCLC; one had squamous cell lung cancer.

In three of these five, their responses (lack of growth of tumor on scans) lasted at least 24 more weeks (about six months).

Six additional patients who did not have an "objective response" nevertheless had stable disease -- and stayed alive -- for at least 24 more weeks.

Oncologists and drug companies like to use "progression-free survival" as an endpoint, and here, it was about 35-50% in the various subgroups of NSCLC at 24 weeks.

The response rates in advanced melanoma were better, with 9 of 52 patients gaining objective responses, and 14 of 52 gaining disease stability for months.

This was a phase I trial of safety. Although 90% had adverse events, the threshold for recording such events is extremely low in a phase I trial (ordinary headaches get counted, for example). Still, this drug was rough on some -- 39% developing rash, hypothyroidism, hepatitis, and isolated cases of diabetes, sarcoidosis or myasthenia gravis. About 5% of patients had serious adverse events.

What It Means

Unfortunately, the industry-funded authors only reported the friendlier progression-free survival statistic rather than the often buzz-killing reality check of absolute survival, which is far lower than PFS in many such trials.

Still, almost any news is good news in the treatment of advanced lung cancer -- and by that criterion, this is Great News. Authors themselves express surprise at their findings, since NSCLC was not felt likely to be sensitive to immune therapies. Rest assured that as you read this, teams of PhDs at Bristol Myers Squibb's Princeton are scrambling to develop a method of identifying which patients with NSCLC would benefit from anti PD-L1 immunotherapy. With that to properly select subjects, followed by a few fast-tracked phase 2 and 3 trials, the promising but excruciatingly slow-motion "revolution" in personalized/molecular/genomic targeting of cancer treatment might have another impressive notch in its belt, and some people with advanced cancers would have another welcome reason for hope.

Brahmer JR et al.Safety and Activity of Anti–PD-L1 Antibody in Patients with Advanced Cancer. NEJM 2012;366:2455-2465.