Dysphagia and swallowing disorders in the ICU (Review)

ICU-related Dysphagia and Swallowing Disorders

More than 700,000 people develop respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation each year in the U.S. alone, and those that survive are at elevated risk for developing swallowing dysfunction. The aspiration syndromes that follow can be devastating, especially if not recognized and addressed early. Denver's Madison Macht et al provide a clinical review of the problem, its diagnosis and management in the October 2013 Critical Care Medicine.

Fun fact: each day, we produce about 700 mL of saliva and swallow over 1,000 times. Aspiration of liquid or solids into the trachea may occur because of impaired swallowing of oral secretions or from gastroesophageal reflux of stomach contents. In ICU patients, an impaired cough mechanism and reduced sensations of regurgitation or dysphagia may make such aspiration "silent" (without signs or symptoms) in more than half of patients with proven aspiration.

ICU-acquired swallowing dysfunction following extubation after mechanical ventilation is a common but under-studied clinical entity. Its true prevalence is unknown, with estimates ranging from 3% to 62%, probably due to high heterogeneity in study designs and populations.

Mechanisms of ICU-acquired Swallowing Disorders

Macht et al describe six potential mechanisms for ICU-acquired dysphagia, swallowing dysfunction, and aspiration syndromes:

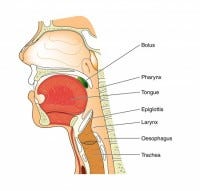

Direct trauma to the anatomy of the throat (vocal cords, tongue base, epiglottis, arytenoids) by endotracheal or tracheostomy tubes

Muscular weakness due to nerve and muscle damage (disuse atrophy; critical illness neuropathy and myopathy)

Loss of normal sensation in the oropharynx and larynx

Impaired sensorium generally (delirium, sedation)

Gastroesophageal reflux

Out-of-sync breathing and swallowing in people with tachypnea before and/or after extubation

Screening for Dysphagia and Swallowing Dysfunction in the ICU

There are no established guidelines or standards of care for routine dysphagia screening among critically ill patients after extubation (other than stroke patients). One survey suggested that less than half of U.S. hospitals routinely screen extubated patients for swallowing dysfunction. There are no good prospective studies to identify useful risk factors or prediction tools to better identify patients who should be tested for swallowing dysfunction after extubation. The decision on screening for dysphagia is left to individual physicians and care teams, who may use arbitrary cutoffs for screening patients who appear at average risk (e.g., those who have been intubated > 24-48 hours).

The most common screening strategy is a water-swallowing test, with someone (a nurse, a speech pathologist, or the physician) observing the patient for signs of aspiration. The aforementioned 50% rate of "silent aspiration" might seem to make this method suspect, but one large study showed the development of aspiration signs or symptoms after swallowing 3 ounces of water was 96.5% sensitive for swallowing dysfunction as detected by gold standard endoscopy performed immediately afterward. However, the 3-ounce water swallowing test has not yet been validated in recently extubated patients in the ICU.

In practice, decisions on whom to screen for swallowing dysfunction after extubation, and how, are made by physicians and care teams on a case by case basis at most hospitals.

How to Diagnose Dysphagia After Extubation

The diagnosis of post-extubation dysphagia is most commonly done with a bedside swallowing evaluation by a speech pathologist. Although this multifaceted test (interview, evaluation of the mouth and cough reflex, and actual swallowing of various food and liquid textures) is a care standard, bedside swallowing tests have had variable sensitivity and low reproducibility when examined in clinical studies. But their relative ease, apparent utility, and noninvasiveness make bedside swallow evaluation the only test performed for most patients.

More advanced tests are generally ordered at the discretion of the speech language pathologist:

Modified barium swallow (videofluoroscopic swallow study) is done in a fluoroscopy suite, where patients swallow foods and liquids of varying consistencies with barium mixed in. A radiologist interprets the test. Observations of the swallowing mechanism are highly variable between radiologists. However, modified barium swallow has high inter-rater reliability for detecting aspiration per se.

Endoscopy (fiberoptic endoscopic swallow study or FEES) can be performed by specially trained speech pathologists, or theoretically anyone skilled in endoscopy. A very small caliber (3.5 mm) endoscope is advanced through a nostril into the pharynx, and the glottis observed on video while the patient swallows. Endoscopy may be still better than modified barium swallow at detecting aspiration (in sensitivity and interobserver variability). Endoscopy can also be done at bedside and visually identify injuries or specific dysfunction. However, FEES endoscopes and trained operators are not widely available.

Post-Extubation Dysphagia: Poorly Understood; Outcomes Unknown

In patients who have never been intubated, the development of aspiration syndromes with pneumonia is known to be a poor prognostic sign. However, the natural course and longer-term outcomes among people with swallowing dysfunction after extubation as they convalesce from an episode of critical illness are unknown (one retrospective observational study, prone to selection bias, showed dysphagia correlated with worse outcomes). Likewise, the efficacy of treatments is also unknown (including enteral feeding tubes, controlling the texture of ingested foods and liquids, speech / swallow therapy, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, botulinum toxin injection, or upper esophageal sphincter myotomy).

Testing for Dysphagia After Extubation: A Recommended Approach

Macht et al recommend the 3-ounce water swallow test as an initial screening test for patients at average risk for swallowing disorders after extubation. Failure is not drinking the entire amount continuously, or coughing or choking up to 1 minute after the test, drooling, gurgling or hoarseness. Anyone failing the 3-ounce water swallow test, or those at higher risk for postextubation dysphagia (patients with "longer" durations of mechanical ventilation; strokes; neuromuscular disease including critical illness polyneuropathy; history of dysphagia, or any previous damage/injury to the airway or esophagus including cancer, surgery or radiation) should get a formal speech language pathology consultation. Those who pass the 3-ounce swallow test should be considered for diet advancement, argue Macht et al.

Madison Macht et al. ICU-Acquired Swallowing Disorders. Critical Care Medicine, October 2013, 41(10): 2396-2405.