Sedation, Analgesia, and Sleep Guideline Update: Melatonin

Reviewing the evidence for the newest PADIS recommendation

Normal sleep patterns aren’t just altered in critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients—often, they’re virtually wiped out by the use of heavy sedatives around the clock.

Natural circadian rhythms are further disrupted by the ICU’s absence of natural light, and frequent awakenings from sleep due to discomfort, noise, and interventions.

Altered melatonin secretion plays a role in these processes, but its contribution is complex and poorly understood. The normal overnight melatonin surge seen in healthy people may be blunted or absent, and melatonin levels may be reduced in critically ill patients. Often, though, melatonin levels are increased overall, especially early in the illness course; this may be an adaptive part of an acute stress response.

The major U.S. critical care society periodically issues guidance on the use of sedation and analgesia in the critically ill. In 2018, they declined to issue a recommendation regarding melatonin to enhance sleep in critically ill adults, citing a very low quality of evidence.

In 2025, they determined there was enough evidence to issue a conditional recommendation, or suggestion, supporting the provision of melatonin to the approximately 5 million adults admitted to ICUs around the world each year.

What changed?

Let’s take a look at the basis for this most recent recommendation regarding melatonin in the ICU.

Melatonin in the ICU: Overview of Randomized Controlled Trials

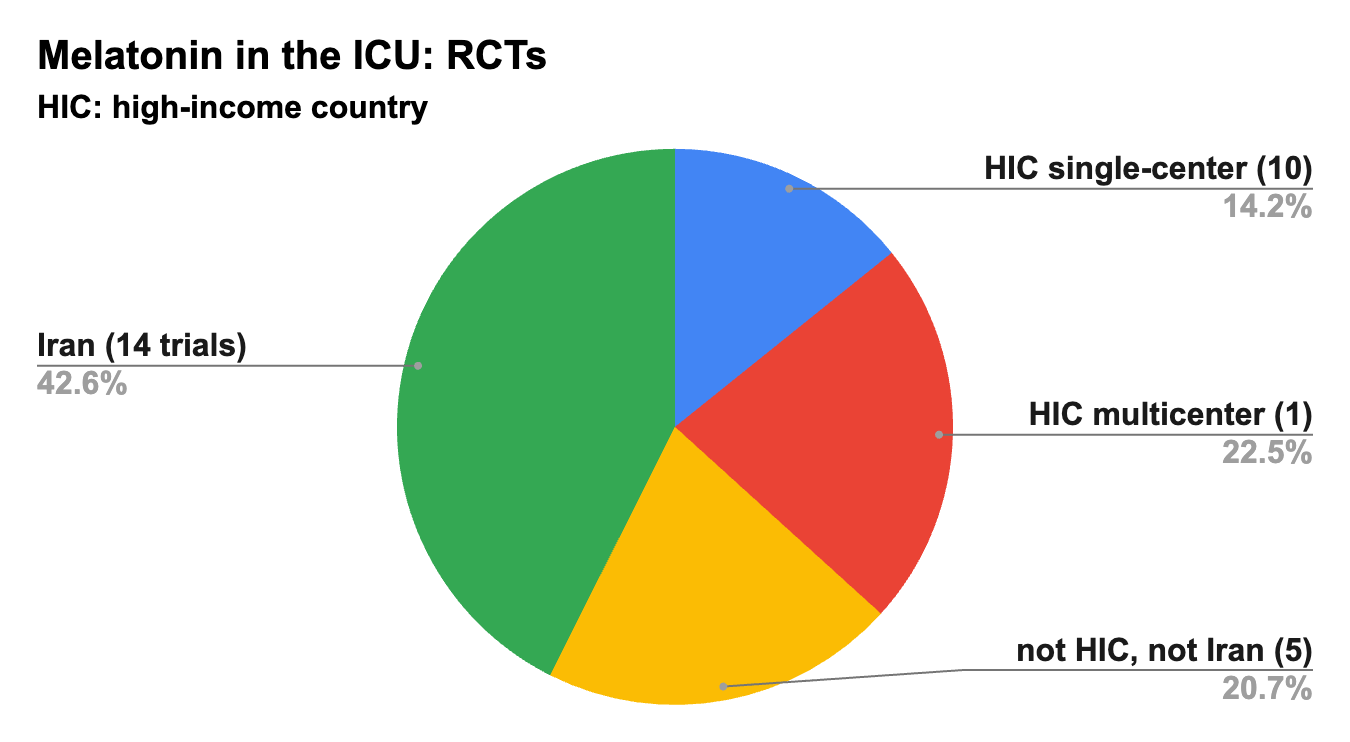

The committee reviewed 30 randomized trials enrolling 3,739 adults, a large majority of which were performed within the past 5 years.

That’s a lot! Let’s examine where and how they were conducted.

There seems to be a particular focus on melatonin research in ICUs in Iran. Almost half of the trials were performed there, encompassing 43% of the patients studied.

The 19 trials conducted in lower-income countries together enrolled 63% of the total number of patients.

Roughly one-third of the total patients were studied in 11 RCTs in high-income countries. Only one of these was a multicenter trial (enrolling about a quarter of all studied patients), while 10 were single-center trials enrolling 12 to 117 patients each.

Most trials (24 of 30) tested melatonin vs. placebo or against no melatonin, but three tested ramelteon vs placebo, two compared melatonin to dexmedetomidine, and one compared melatonin with benzodiazepines.

Melatonin to Improve Sleep in the ICU

The pooled analysis did not find melatonin improved sleep in the ICU.

The mean difference was +2.4 minutes of sleep overnight, with a 95% confidence interval of 10 minutes less sleep to 15 minutes more.

This outcome was usually patient-reported sleep, which is believed to be an unreliable measure of sleep.

Melatonin and “ICU Delirium”

The committee concluded that melatonin might reduce the prevalence of delirium in the ICU.

The pooled relative risk for delirium among melatonin-takers was 0.70, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.57–0.87.

They graded this as low certainty.

How low, we might ask?

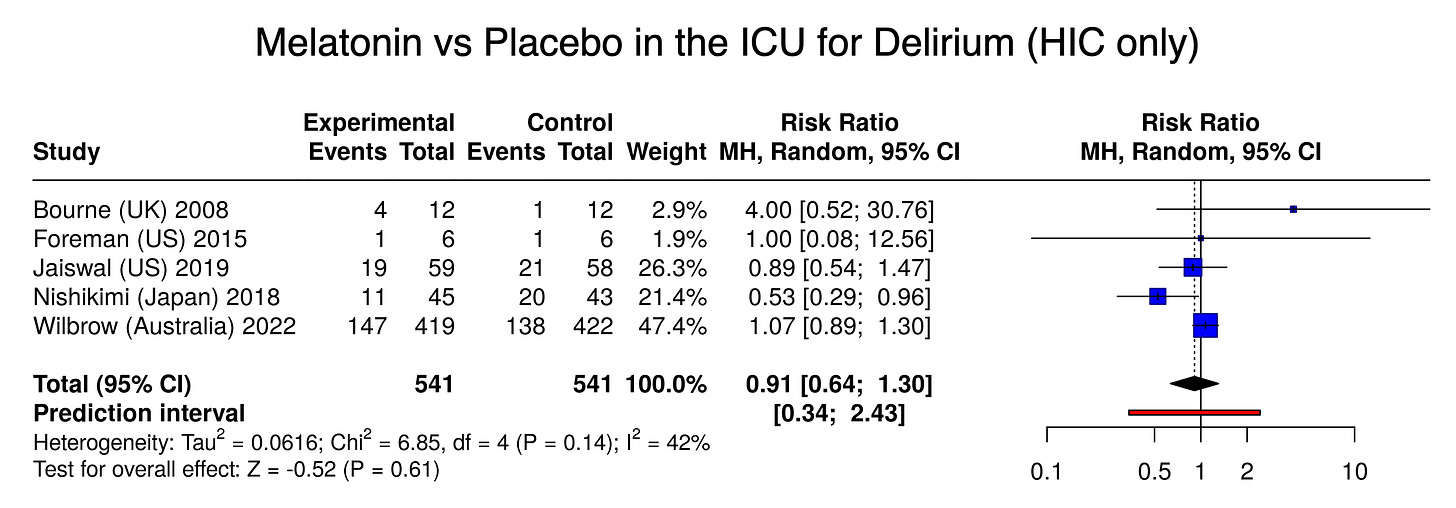

One way to look more closely is to analyze the trials into two tranches: those that were performed in high-income countries, and those that were not.

Melatonin’s Effect on Delirium: RCTs in High-Income Countries

In the only multicenter trial in a high-income country (Wilbrow et al Intensive Care Med 2022), conducted at 12 ICUs in Australia, patients were assessed for delirium twice daily with the CAM-ICU tool.

Among those receiving melatonin, 79.2% had positive CAM-ICU screenings, vs. 80% of those receiving placebo. There were no differences in other outcomes either.

Adding in the four single-center studies performed in high-income countries that reported delirium as an outcome (n=1,082), we get this forest plot (click the image and rotate your mobile device for a better view):

This produces a relative risk for delirium in the melatonin arms of 0.91 (95% CI 0.64 to 1.30), not significant.

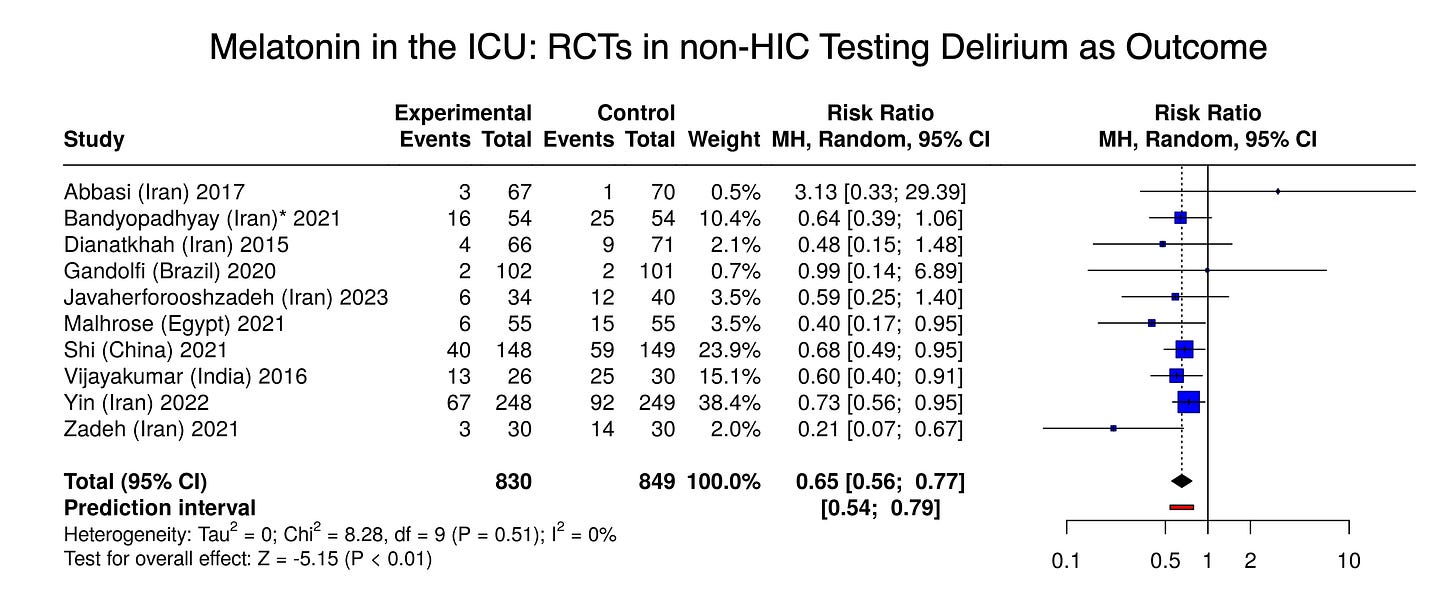

Melatonin’s Effect on Delirium: RCTs In Lower-Income Countries

Now let’s combine the studies conducted outside high-income countries that tested melatonin vs placebo or no melatonin for the outcome of delirium (n=1,679):

In published randomized trials conducted in non-high-income countries, melatonin nearly always showed a strong effect toward reducing delirium in the ICU, with a very large pooled relative risk reduction of 35%, highly statistically significant.

This divergence from the signal in high-income countries strongly suggests publication bias, or other bias or methodological issues affecting some or most of the studies’ results.

(Ironically, the null finding by Gandolfi et al in Brazil was down-weighted in this random-effects analysis as an outlier.)

Melatonin’s Effect on Other Outcomes

The committee reported that “melatonin may slightly reduce the length of ICU stay” by 12 hours.

We’ll skip the forest plot on this one, but consider the fact that 11 of the 14 trials outside high-income countries reported numerical reductions in ICU stay in their melatonin group.

In high-income countries, only one of the six trials reported a numerical reduction in ICU stays with melatonin use (non-significant), and the pooled estimate (by eyeball test) showed no difference.

Also, consider the intuitive plausibility of the claim that giving melatonin reduces ICU stays.

There were no other measurable effects from melatonin in the ICU.

Limitations

Trials measuring sleep used patient-reported sleep as the outcome, not sleep studies or EEG. Subjective recall of sleep duration is believed to be unreliable.

Conclusions

Critically ill patients experience serious sleep disruptions for a variety of reasons. Their overnight secretion of melatonin is also often disrupted (although not always low).

In a 2025 update to its clinical guidelines, the major U.S. critical care society suggests melatonin be provided to the ~5 million adults admitted to ICUs each year, on the premise that it might improve delirium, sleep quality, and reduce ICU stays.

A critical analysis of the literature supporting this suggestion finds no convincing evidence for those benefits.

However, melatonin might help and seems to pose little risk.

Melatonin is not FDA-regulated. As melatonin in the trials varied in dose and frequency (often 3 mg daily), a specific melatonin dosage was not advised.

Thank you for this analysis.