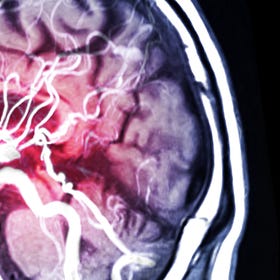

Should thrombolytics be given >4.5 hours after stroke onset?

Improved outcomes despite intracranial hemorrhages in a new meta-analysis

Neurologists’ job just got harder.

Patients who present with ischemic stroke more than 4.5 hours after symptom onset generally do not receive intravenous thrombolytics (tPA or TNK). That’s because outside that accepted window, the risk of intracranial hemorrhage was believed to outweigh the benefits of thrombolytics in restoring blood flow to at-risk brain tissue.

A new meta-analysis challenges that dogma, and makes an already challenging decision-making process even thornier for neurologists answering “code strokes”.

At least 8 randomized trials have been published testing IV thrombolytics given more than 4.5 hours after stroke symptom onset. None of the enrolled patients underwent mechanical thrombectomy (that was tested in other trials), and all underwent specialized brain imaging studies to ensure they had salvageable brain tissue.

We reviewed one of them, TRACE-III here:

Tenecteplase (TNK) for ischemic stroke after 4 hours

Tenecteplase (TNK) has become standard therapy at many centers for ischemic stroke presenting within 4.5 hours of symptom onset. TNK’s advantages over alteplase (tPA) include easier administration (single bolus dosing instead of bolus-plus-one-hour infusion), arguably superior pharmacokinetics (greater binding to fibrin), and association with improved o…

Three of the 8 originally showed a statistically significant benefit of thrombolytics given after 4.5 hours; the others were inconclusive with wide confidence intervals.

In a meta-analysis published in Stroke, however, aggregating the 8 trials (n=1,742) led to a positive finding of improved neurologic outcomes overall for patients treated with thrombolytics given more than 4.5 hours after stroke onset (without thrombectomy):

An odds ratio of 1.43 (95% CI 1.17-1.75) for excellent functional outcomes;

An odds ratio of 1.36 (CI 1.12-1.66) for good neurologic outcomes.

Running their numbers through metaanalysisonline.com using the authors’ described methods but with hazard ratio as the output produces a smaller effect size of 1.28, but still significant.

These benefits came at the price of (and despite) an increased risk of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (odds ratio 4.25, CI 1.67-10.84).

The odds ratio for mortality at 90 days was 1.28 in the group given thrombolytics, but this was not statistically significant (CI 0.87-1.89).

These trials all used advanced imaging techniques to identify patients who might have salvageable brain tissue: either perfusion imaging (CT/MRI) or diffusion-weighted imaging (MRI).

These imaging modalities are not rapidly available during “code strokes” in most community centers, which rely solely on non-contrast CT to make treatment decisions for ischemic stroke.

Discussion

For patients arriving at stroke centers where advanced imaging is rapidly available, neurologists now face even more nerve-wracking choices on whether and which late-presenting patients should be provided thrombolytics. It’s straightforward to look at the overall numbers and rationally conclude, “thrombolytics help.” It’s not so easy to face a patient and family after seeming to have caused a symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage—especially when one is treating slightly outside the commonly accepted care standard.

For patients presenting in the community late after their stroke onset, who previously were considered non-candidates for thrombolysis, management also becomes more complex. Late thrombectomy (without thrombolysis) has been shown to be beneficial and often leads to rapid transport to a stroke center after a teleconsultation with a neurologist or neuroradiologist. Should those patients now receive thrombolytics at the remote location prior to transport, sight unseen by the accepting team? Absent perfusion imaging, it seems unlikely this will be advised.

Conclusions

Thrombolytics given more than 4.5 hours after stroke onset appear beneficial in patients with ischemic stroke who have not undergone thrombectomy, in whom specialized imaging confirms salvageable brain tissue.

Advances in stroke care are happening faster than expert consensus can develop, which is not a bad problem to have. The diminishing benefits and competing risks of thrombolytics will demand careful individualized management for patients with late-presenting ischemic strokes.

References

Late Thrombolysis-Without-Thrombectomy RCTs:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30947642/

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12975-024-01231-2

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1813046

https://j-stroke.org/journal/view.php?doi=10.5853/jos.2023.00668

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.028127

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa2402980

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1804355

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/strokeaha.110.580464

Literature is fine. Real world practice is quite another thing. The risk of bleeding is super high (look at the upper limit of the confidence interval). Glad I’m not a Tele neurologist lol.