The Latest in Critical Care: October 27, 2025

Do interventional pulmonologist fellows steal cases? STAMINA trial. Music in the ICU.

Interventional pulmonologists steal cases, diminish fellows’ bronchoscopy skills? Not so fast

Pulmonary/critical care fellows who were trained at sites with an IP fellow scored significantly lower on measures of bronchoscopy skills, compared to fellows training at sites without IP fellows, a new study showed.

On its surface, the study seemed to suggest that IP fellows took bronchoscopy cases that regular fellows would otherwise perform. For example, most fellows (72%) at non-IP programs had performed more than 100 bronchoscopies, while only one fellow (4%) at an IP program had performed that many.

Fellows’ skills scores were directly proportional to the number of bronchoscopies performed, suggesting that the loss of valuable training cases to the IP fellows reduced their skills. The findings were even presented at a national meeting.

However, a cursory glance at Table 1 reveals that first-year fellows were significantly overrepresented in the assessed cohort at IP centers (60%), while only 16% of the fellows assessed at non-IP centers were first-years.

In other words, the fellows assessed at non-IP programs were further along in their training, had performed many more procedures, and had higher measured bronchoscopy skills.

When adjusted for training level, fellows at non-IP programs had better assessed skills in their second year, but not in their first or third years.

Bronchoscopy scores were measured by the Ontario Bronschoscopy Assessment Tool. An OBAT score of 4.54 has been proposed as being associated with competence on bronchoscopy. Fellows at IP programs scored only 3.53, compared to 4.33 at the non-IP centers overall — but with an unequal distribution of experience among the tested fellows, this metric was essentially meaningless.

Only five centers participated in the small study: two with IP fellowships (Mt. Sinai in NYC and U. of Pennsylvania) and three without (U. of Tennessee-Knoxville, U. of Michigan, and University in Cleveland).

The STAMINA trial was ironically named, it turns out

The STAMINA trial enrolled patients in Brazil with severe pneumonia and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (aka ARDS), randomizing them to a dynamic strategy limiting the driving pressure (= plateau pressure minus PEEP, representing the distending pressure on the lung with each breath) or a strategy limiting PEEP.

The protocol for the intervention arm was a respiratory physiology lover’s dream come true.

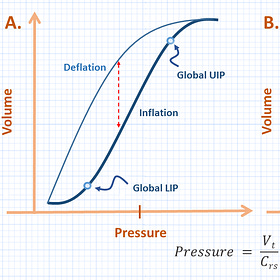

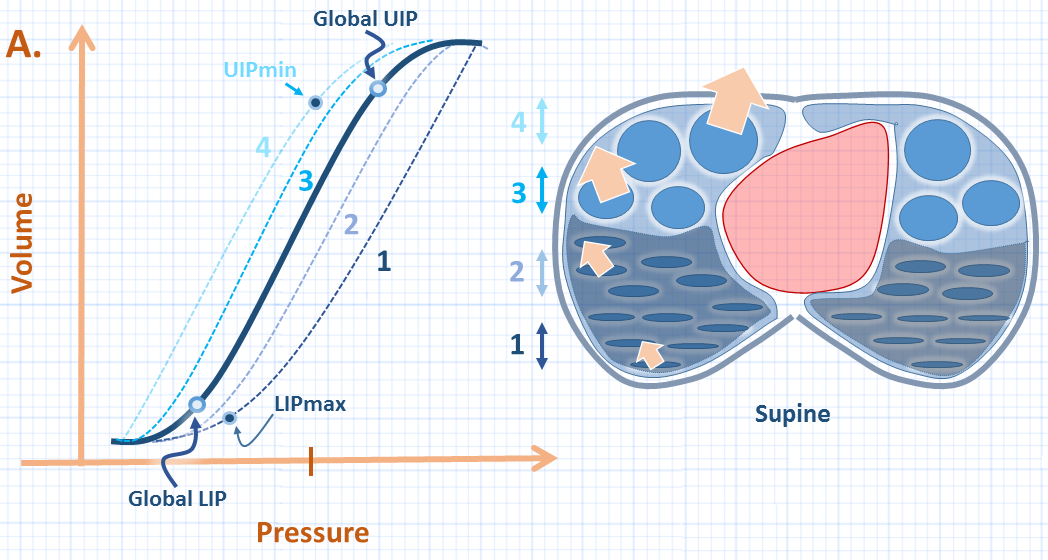

Lung compliance increases with the level of PEEP applied, statrting at a lower inflection point (LIP) up to an upper inflection point (UIP) at which compliance decreases, reflecting overdistension.

ICU Physiology in 1000 Words: The Respiratory System Pressure-Volume Curve

Jon-Emile S. Kenny MD [@heart_lung]

In STAMINA, PEEP was individually titrated for each patient to optimize their compliance. Once their optimal PEEP was set, their tidal volumes were reduced to reduce driving pressure to the lowest level that could support adequate gas exchange.

For control arm patients, PEEP was titrated according to a low PEEP:FiO2 ARDS table (e.g., PEEP 5 for FiO2 30%, up to PEEP 18-24 for FiO2 100%).

Plateau pressure ≤30 cm H2O was targeted for all patients.

Target enrollment was 500, but STAMINA was stopped early from “recruitment fatigue” after 214 patients were enrolled.

Among the 198 available for analysis, there were no differences between groups in ventilator-free days (6 vs 7, P=0.28).

The underpowering produced an absence of evidence, rather than evidence of absence, and the possibility remains that a driving pressure-guided strategy could improve outcomes.

When they won’t stop playing that song you hate

A 2014 Cochrane review of 14 randomized trials concluded that playing music through headphones to people receiving mechanical ventilation reduces their systolic blood pressure and respiratory rate, and might reduce their need for sedatives and anxiolytic drugs.

In a new randomized trial, among 158 mechanically ventilated older adults randomized to hear slow-tempo music or silence through noise-cancelling headphones, music did not reduce coma or delirium, pain, or anxiety, using conventional scales and scores.

The playlists were chosen by a music therapist, including classical music as well as lyric-free “contemporary relaxing tracks” starting at 80 beats per minute and transitioning down DJ-style to songs at 60 beats per minute, all “carefully selected to provide a homogenous and cohesive slow-tempo music listening experience.”

But could patients have deliberately acted comatose or delirious to protest being forced to listen to Muzak™? The authors do not account for this possibility.

To withhold your consent from future participation in any such study and ensure that your personal musical taste is respected, update your advance directive or notify your surrogate decision maker.

The Potential of Music as a Nonpharmacologic Intervention for the ICU—Sound Medicine

Music interventions for mechanically ventilated patients - Bradt, J - 2014 | Cochrane Library