THE REAL-WORLD BOARDS: Question #1

An 82-year-old woman in refractory V-fib arrest arrives in the E.D. Your move.

These are the Real-World Boards. As in the real world, there might be no single right answer, and you are only competing against yourself. Please share your experiences, discuss and critique this question below. Good luck! -Ed.

An 82-year-old woman is brought from a nursing home by EMS to the emergency department in ventricular fibrillation. She was found unresponsive about 15 minutes ago after an unknown period. Chest compressions were begun on site immediately and were continued throughout transport. Pre-hospital, she received ACLS-guided resuscitation with regular epinephrine injections and at least 5 shocks, first by the on-site AED and then by EMS, delivering 200 joules by a biphasic defibrillator.

Your emergency medicine colleague has continued high-quality CPR and epinephrine and delivered three additional shocks, escalating to 300 J and then 360 J in the E.D.

Amiodarone (300 mg and then 150 mg IV) was given. The original pads’ correct anterolateral position and function were confirmed.

She remains in ventricular fibrillation. There have been no ST-elevations noted and no morphology to suggest torsades de pointes. No reversible causes have been identified on labs or exam. Approximately 20 minutes have elapsed since the initiation of CPR. Attempts to reach the family have been unsuccessful. The patient is in a “full code” status.

By telephone, the on-call cardiologist recommended against left heart catheterization due to the predicted poor outcome even if occlusions were found and revascularization were to permit defibrillation.

Your emergency medicine colleague asks your opinion on what to do next.

Physicians receive no formal guidance on how long to perform CPR. Although the median duration is ~20-25 minutes in the U.S., this masks a wide variability that is influenced by multiple poorly understood factors: the culture at the institution; the physician’s habits acquired in training; her personal values and religious beliefs; perception of a patient’s life expectancy and expected outcome, and more.

Refractory ventricular fibrillation poses unique challenges to the treating physician. Unlike the non-shockable rhythms (asystole and pulseless electrical activity), VF is often due to reversible causes, and patients overall have better outcomes when the arrhythmia is terminated.

All other things being equal, therefore, it is reasonable to take a more aggressive or “heroic” approach to treating refractory VF, as compared to asystole or PEA.

After all, a resuscitation failure is equivalent to death. Yet the very term aggressive implies an edge of extremity, a risk of harm. And most of the improvement in outcomes with shockable rhythms comes when they are terminated early.

Can one go too far while treating a cardiac arrest?

Dual Sequential Defibrillation

Dual sequential defibrillation involves delivering two defibrillation shocks in rapid sequence using two defibrillators, each connected to its own set of pads. Double sequential external defibrillation (DSED) is another moniker.

For a patient already undergoing resuscitation, a second set of defibrillator pads is placed in a different vector (e.g. anterior-posterior) than the existing set of pads (usually in the standard anterolateral vector).

Both defibrillators are charged to maximum energy (usually 200 J on biphasic devices, but possibly higher), and the two shocks are delivered in very quick succession (e.g., ~10 milliseconds apart, but not perfectly simultaneously).

Shocking more myocardium in more than one vector could theoretically terminate VF more effectively than a single vector.

In the DOSE VF trial (Cheskes et al, NEJM 2022), patients with refractory VF randomized to dual sequential defibrillation had greater survival to hospital discharge and improved neurologic outcomes compared to conventional defibrillation. DSD was administered by EMS in the pre-hospital setting. The trial was stopped at about half the intended enrollment due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The American Heart Association’s 2020 ACLS guidance gave a 2b recommendation for DSD (“may / might be considered”), citing a 2020 systematic review by ILCOR that found insufficient evidence to support DSD.

AHA expressed concerns about proper implementation and potential for harm to patients or damage to defibrillators, stating:

“It is premature for double sequential defibrillation to be incorporated into routine clinical practice given the lack of evidence. Its usefulness should be explored in the context of clinical trials.”

Notably, the DOSE VF trial had not yet been published at that time.

ILCOR (which advises AHA and similar societies) gave a weak recommendation for DSD for refractory VF/VT in a 2023 statement (after the publication of DOSE VF).

A randomized trial in Norway testing DSD for VF with an intended enrollment of 356 patients is underway, according to clinicaltrials.gov.

Video by EM:RAP via YouTube provided here for informational purposes only. -Ed.

Stellate Ganglion Block

Some refractory VF is caused or exacerbated by excessive autonomic (sympathetic) nervous system activity, called electrical storm.

In a stellate ganglion block, local anesthetic is injected near the stellate ganglion, a collection of sympathetic nerves located in the neck (at the level of the C6 or C7 vertebra). SGB has an established role in the treatment of chronic pain; anesthesia and pain specialists may perform the block when sympathetic activity is believed to be worsening a patient’s pain syndrome.

SGB has also been used experimentally as a treatment for refractory shockable rhythms (ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation). Blocking the stellate ganglion reduces sympathetic outflow to the heart, potentially reducing arrhythmogenic triggers.

Lifelong Learners: continue reading to receive prompts and a link to earn CME credit for reflecting on this educational activity via your included Learner+ access.

In an observational case series of 30 consecutive patients with drug-and-shock-refractory electrical storm (most with ventricular tachycardia) who received percutaneous stellate ganglion blocks (bupivacaine +/- lidocaine) from 2013 to 2018, 60% had resolution of arrhythmias within 24 hours. (Tian et al, Circulation Arrhythmia & EP 2019)

Similar effectiveness for SGB was later reported among 117 patients at Duke and IKEM in the Czech Republic. Most (70%) had refractory VT in this retrospective case series. (Chouari et al, JACC Clin EP 2024)

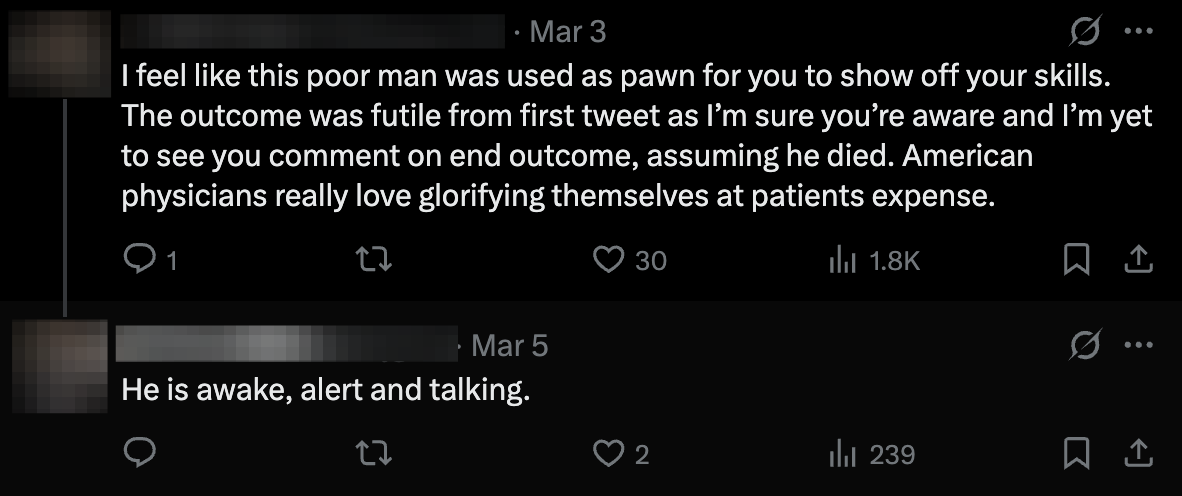

X/MedTwitter erupted in 2025 when a U.S. emergency physician described performing SGB on an elderly patient with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest from refractory VF.

After dual sequential defibrillation failed, the physician performed a stellate ganglion block.

Reactions were mixed:

The following video (by Regional Anesthesiology and Acute Pain Medicine via YouTube) is provided for informational purposes only:

Stellate ganglion block is considered an experimental therapy for refractory VF or VT. Neither AHA nor ILCOR comment on the treatment in their most recent guidance.

The multicenter randomized STAR trial is enrolling up to 500 patients to test SGB as a treatment for refractory VF at 38 centers in Italy, according to clinicaltrials.gov.

Reflect to earn CME with Learner+

Suggested reflection: I read about experimental therapies for patients in refractory ventricular fibrillation: dual sequential defibrillation and stellate ganglion block.

Continue CPR or Start ECPR

There is no consensus on how long to perform conventional ACLS-guided resuscitation.

ECPR (extracorporeal CPR) is usually V-A ECMO (veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) initiated on a patient in cardiac arrest (usually due to VF/VT), with large-bore cannulae inserted into the femoral vein (to drain deoxygenated blood) and femoral artery (to return oxygenated blood).

For patients with cardiac arrest due to acute occlusive myocardial infarction, ECPR can buy precious time to preserve cerebral blood flow until revascularization with percutaneous coronary interventions can be performed.

ECPR requires advanced equipment and specialized personnel, and is offered only at centers with established protocols for patient selection and rapid cannulation.

In 2024, an emergency physician writing for the New York Times announced to the public that

“patients with certain types of cardiac arrest who are treated with a new procedure, called ECPR, have a nearly 100 percent chance of being revived, with their brain function intact, if treatment is administered within 30 minutes of collapse.”

This was based on the reported experience at the University of Minnesota’s Center for Resuscitation Medicine, created around 2014 by interventional cardiologist Dr. Demetris Yannopoulos. In the ARREST trial (n=30), 43% of patients with refractory VF randomized to ECPR survived to hospital discharge, vs. 7% of those treated conventionally; the trial was stopped prematurely due to certainty of benefit.

(It’s unclear where the “nearly 100 percent chance” the physician-journalist cited came from. Dr. Yannopolous himself has only claimed at best a 75-80% survival for patients cannulated within ~7 minutes, which is already amazing, so why exaggerate?)

Outcomes with ECPR may be highly center-dependent. Its most impressive initial results have not been replicated elsewhere.

ECPR was not shown to be superior to conventional CPR in the subsequent multicenter INCEPTION trial in the Netherlands, where 20% of ECPR patients vs. 16% of conventional CPR patients survived to 30 days with good neurologic outcome (not statistically significant);

Nor was ECPR clearly superior in a trial in the Czech Republic (Behlolavek et al JAMA 2022), in which survival at 180 days with good neurologic function was 31.5% with ECPR vs. 22% with standard care (P=0.09).

All three RCTs testing ECPR did show nominally improved outcomes with ECPR, although the latter two did not reach significance.

However, ECPR was arguably not implemented as effectively in the two negative RCTs. ECPR in those trials was initiated significantly later than in the ARREST trial, and patients were not maintained on ECPR as long.

The 2020 AHA guidelines give ECPR a 2b recommendation (“may be considered if there is a potentially reversible cause of an arrest that would benefit from temporary cardiorespiratory support”).

Stop CPR and Declare Death

There’s no “good” or “right” time to stop CPR. How does one decide?

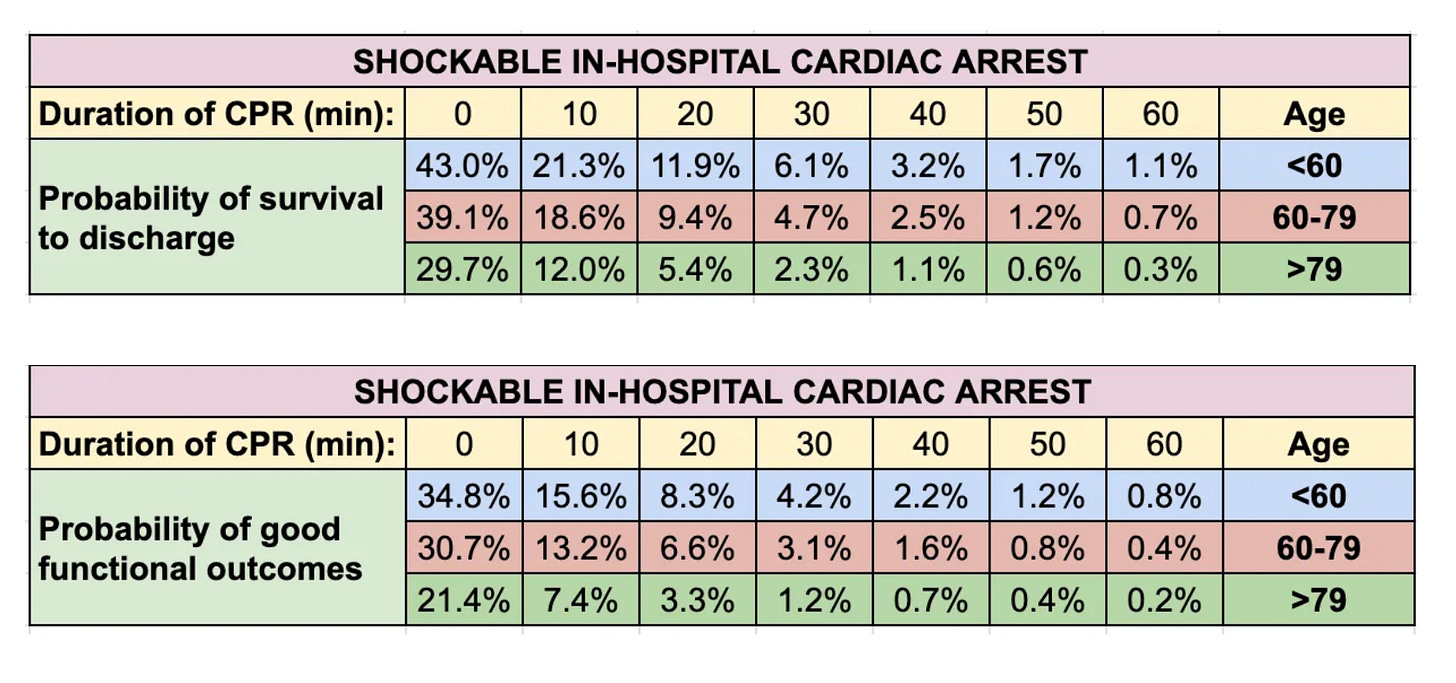

Hospitals participating in the AHA’s Get With The Guidelines program and registry have generated empirical data on outcomes for ~350,000 adults with in-hospital cardiac arrest (2000-2021).

Here is the survival data for witnessed shockable cardiac arrests occurring in the hospital:

And for survival with good functional outcomes:

If resuscitated at 20 minutes of CPR after an in-hospital witnessed shockable arrest, an 82-year-old woman has a ~1 in 20 chance of survival, and a ~1 in 30 chance of surviving with a good neurologic outcome. Probabilities decline steeply with increasing duration of arrest.

Outcomes after out-of-hospital arrests, non-shockable rhythms, and/or unwitnessed arrests are worse.

These figures may be spuriously low due to prophecy-fulfillment bias (when CPR was abandoned in patients who would have survived).

When to stop CPR is a difficult decision that should be “patient-centered,” but owing to the circumstances, rarely can be. We touched on some of that complexity in our ongoing series:

Advocate for Left Heart Cath and Revascularization

Many cardiac arrests with refractory ventricular fibrillation or tachycardia are precipitated by acute occlusive myocardial infarction, a.k.a. ST-elevation MI.

However, interventional cardiologists do not perform emergent left heart catheterization on a patient receiving active conventional CPR, not least because high-quality chest compressions make the procedure technically challenging or impossible.

Patients receiving ECPR (ECMO) can undergo emergent cath with revascularization. Evidence for this approach is limited, but centers with a high level of institutional dedication to this strategy have reported results better than would be expected for out-of-hospital cardiac arrests.

Patients who benefit tend to have witnessed VF/VT arrest, minimal downtime, and rapid ECMO cannulation and coronary reperfusion (within ~60 minutes of collapse).

Other Considerations

Lidocaine

Either amiodarone or lidocaine should be given in most patients with cardiac arrest due to VF/VT that is unresponsive to shocks and epinephrine, with amiodarone generally preferred. AHA guidelines (2020) do not recommend routine use of both agents sequentially, but retrospective studies and case reports have described the adjunctive use of lidocaine after amiodarone has failed in refractory VF/VT.

No randomized trials support this strategy, and lidocaine should be considered experimental in this setting.

Esmolol

Esmolol, an ultra–short-acting β1-selective blocker, can reduce sympathetic activity theoretically contributing to refractory VF/VT. Esmolol lacks good evidence to support its use (or to confirm it is not helpful). A 2016 single-center retrospective study reported use of a 500 mcg/kg bolus followed by a 0-100 mcg/kg/min infusion, with some success in achieving ROSC. As of 2024, there were no RCTs to support this use of esmolol, which is considered off-label and experimental.

Reflect to earn CME with Learner+

Suggested reflection: I read about the management of patients in refractory ventricular fibrillation (and VT), including various experimental therapies that can be considered when ACLS-guided resuscitation is unsuccessful. Decision-making for refractory VF/VT is complex and influenced by patient factors as well as the limited evidence supporting the therapeutic options.

This is truly fantastic!!! Great post, very insightly.