(UNLOCKED) The Real-World Boards: Question #20

A 62-year-old female goes into wide-complex tachycardia on the med/surg floor

These are the Real-World Boards. As in the real world, there may be no single “right” answer, and you are only competing against yourself. Upgrade to the Lifelong Learner level for full access to all the questions and unlimited CME credits with an included Learner+ account.

I’m delighted to share this guest Real-World Boards Question from Lloyd Tannenbaum, MD, who authors the fantastic ECG Teaching Cases on Substack.

A 62-year-old female is admitted to the med/surg floor for a high-risk NSTEMI. In the ER, she had nonspecific ST-T wave changes on her ECG and an elevated high-sensitivity troponin. She is pending a cardiac catheterization tomorrow morning with interventional cardiology, but goes into a wide-complex tachycardia on the floor. The nursing team calls a code blue, and you respond to find a conscious, uncomfortable-appearing woman who is not in severe distress.

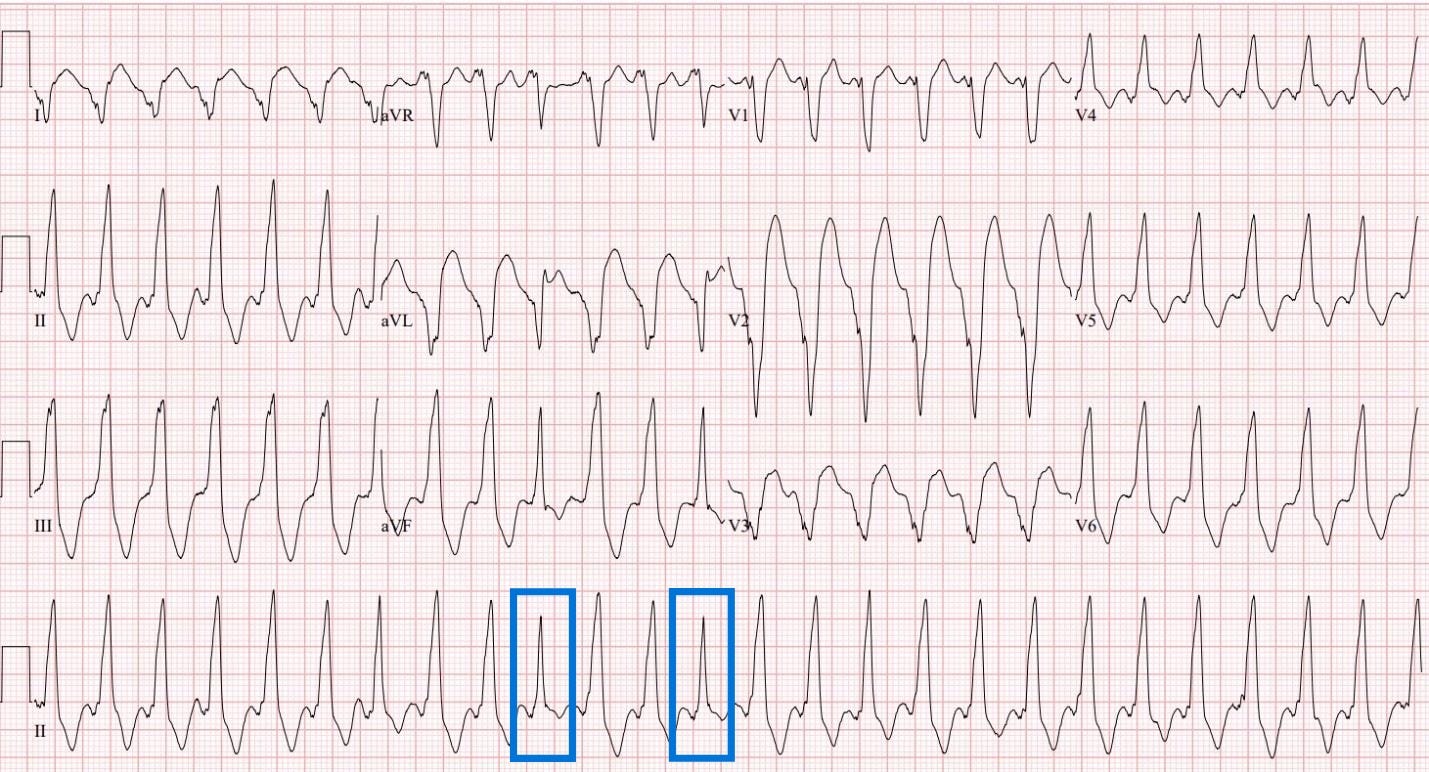

The admitting team hands you the following ECG and asks for your assistance in managing the patient:

You take a look at the ECG and read it as:

Rate: 150-160

Rhythm: Not sinus rhythm, no obvious P waves, not coming from the sinoatrial node

Axis: a little tricky. With aVR being negative and II, III, and aVF being positive, the axis is likely between normal and rightward deviated. As we’ll see, this is a bit atypical for this condition.

Intervals: Wide complex QRS, no PR intervals

Morphology: The 10th and 13th beats look different (blue box). They’re not truly sinus beats, but not quite ventricular either.

You discuss the patient with the admitting medicine team, and they are very concerned. She’s currently hemodynamically stable with a blood pressure of 130/85, respiratory rate of 16, oxygen saturation of 99% on room air, and afebrile. The medicine team asks your opinion on what to do next.

Final read: This is a wide complex tachycardia with fusion beats (10th and 13th beats). This ECG is showing ventricular tachycardia (Vtach) with a rightward/normal axis. Fusion beats would push for a diagnosis of Vtach over SVT with aberrancy. Usually, we’d expect a leftward axis with Vtach or a “northwest” axis (between -90 to 180), given that the electrical impulses originate from the ventricles, but in this case, the axis is somewhere between rightward and normal.

The patient is currently hemodynamically stable, so this is stable Vtach.

Optimal management of stable Vtach has been the subject of multiple (small sample size) trials, the most widely cited of which is the PROCAMIO trial. In this study, patients in hemodynamically stable Vtach were randomized into either the procainamide arm or the amiodarone arm. The study found that of the 33 patients given procainamide, 22 (67%) converted out of their wide complex tachycardia, as opposed to 11 of the 29 (38%) in the amiodarone group. While this is good knowledge to know, conversion out of the wide complex rhythm wasn’t the primary endpoint of this study; rather, it was major adverse effects 40 minutes after drug administration. Researchers found that amiodarone had significantly more adverse effects than the procainamide group, including 6 of the 29 (21%) requiring emergent DC cardioversion due to hypotension. The conclusion of the PROCAMIO study was “Procainamide therapy was associated with fewer major cardiac adverse events and a higher proportion of tachycardia termination within 40 min.”

But don’t just believe one study. Multiple other studies looked for the best medication to treat stable Vtach. This chart nicely summarizes them and comes from an article published in the Journal of Emergency Medicine in 2017. We’re going to walk through these trials together.

The first trial was published in Lancet in 1994 by Ho et al. In this trial, 33 patients with hemodynamically stable Vtach were randomized to receive either 100 mg IV lidocaine or 100 mg IV sotalol. Their primary outcome was termination of Vtach within 15 minutes of receiving the drug. In this study, 69% of patients given sotalol converted out of Vtach, while only 18% of those given lidocaine converted.

In 1996, Gorgels et al ran a trial looking at lidocaine compared to procainamide for the termination of stable Vtach. The primary outcome again was termination of VTach 15 minutes after drug administration. In this trial, procainamide was successful 80% of the time, while lidocaine was only successful 21% of the time. Interestingly, in this study, the authors used procainamide as a rescue drug when lidocaine wasn’t effective in converting patients out of Vtach.

Manz et al looked at ajmaline compared to lidocaine for the termination of Vtach. Ajmaline is a class 1a antiarrhythmic that’s more potent than procainamide. It’s actually often used as a “sodium channel blockade challenge” to confirm the diagnosis of Brugada Syndrome in the EP lab. Most likely, we won’t be ordering ajmaline on the floor to treat stable Vtach, but if we did, it had a 67% success rate compared to lidocaine’s 13%.

There was a study in 2010 by Drs. Marill et al that looked at amiodarone and procainamide for the termination of stable Vtach before the PROCAMIO trial was started. This was a retrospective study, so the authors looked back at patients given amiodarone or procainamide and recorded if the arrhythmia terminated 20 minutes after drug administration. They found that procainamide had a success rate of 30% whereas amiodarone only had 25%. Interestingly, this trial also notes that 6% of patients getting amiodarone and 19% of patients getting procainamide developed hypotension and required immediate DC cardioversion. This is one of the major papers to question the efficacy of medical therapy for Vtach as they conclude that, “Both agents were relatively ineffective and associated with clinically important proportions of patients with decreased blood pressure.

Finally, Dr. Komura et al looked at lidocaine and procainamide, and again, the results are very similar. Lidocaine terminated VT 35% of the time, while procainamide terminated it 75% of the time. Again, procainamide was used as a rescue if lidocaine was ineffective and converted an additional 4 patients out of VT that lidocaine didn’t fix. This trial included 90 patients and was also a retrospective case series.

The last study in the table is actually the PROCAMIO trial, which we already talked about.

So, what can we conclude from all of this? Medications are an option to treat stable ventricular tachycardia, but they aren’t a great option.

Can we consider DC cardioversion of these patients, even though they are hemodynamically stable? Yes!

Guidelines from the AHA, ACC and Heart Rhythm Society all endorse synchronized DC cardioversion of stable Vtach if antiarrhythmic drugs fail or are not appropriate for any reason. Synchronized cardioversion has the advantage of potentially immediate resolution for patients who are symptomatic or at risk for becoming unstable.

Cardioversion for stable ventricular tachycardia should be synchronized to the QRS complex to minimize the risk of inducing ventricular fibrillation.

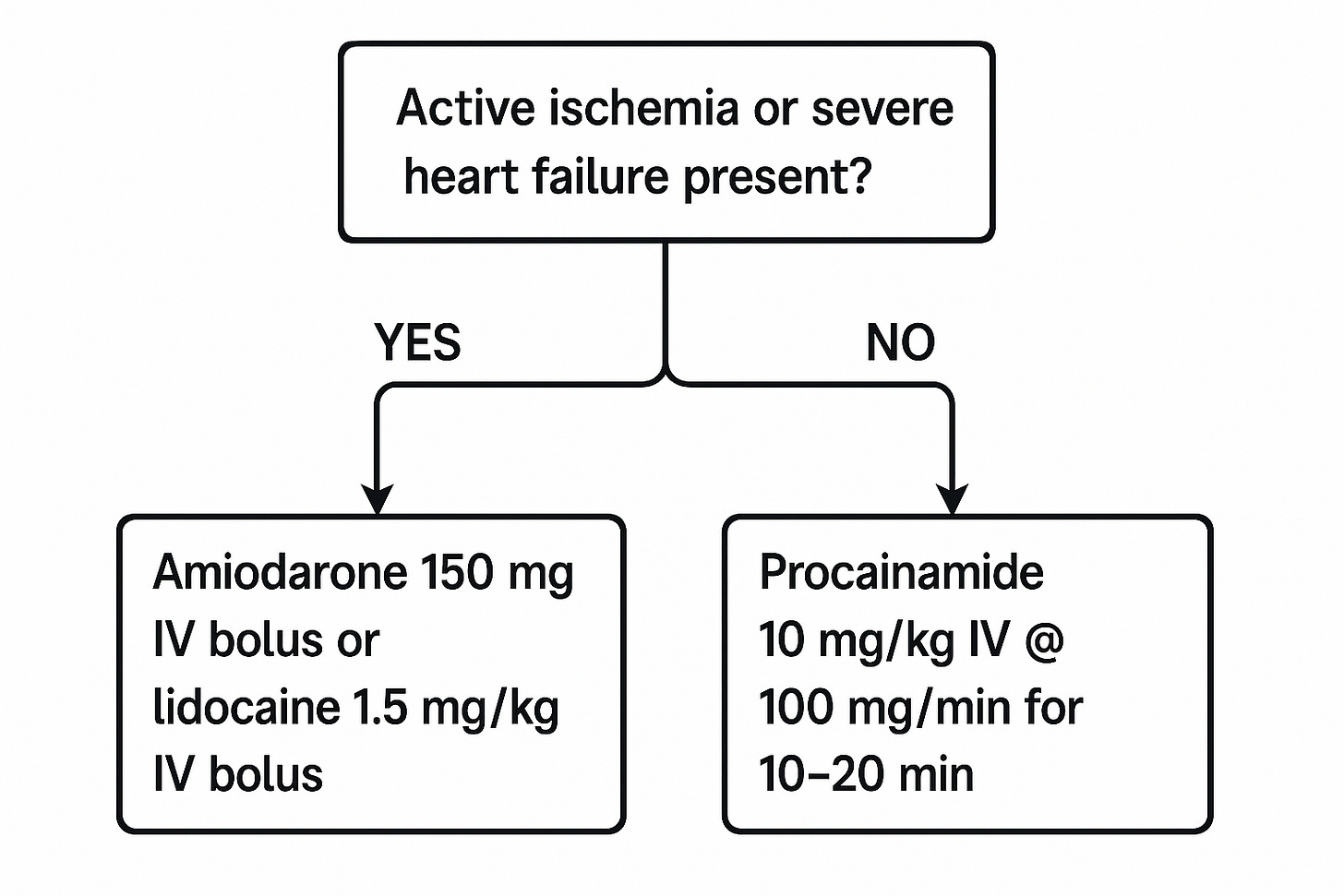

Take a look at this flowsheet, adapted from Long and Kofyman’s 2017 Vtach review. It may be worth running through this in your head the next time you’re called to the floor to treat a patient in stable Vtach.

This assumes the patient has IV access, is on a monitor, and has a 12-lead ECG completed, with cardiology consultation requested.

If the patient remains hemodynamically stable but does not opt for cardioversion with sedation:

Let’s put this all together:

The data behind medications terminating stable Vtach is not great

It is reasonable to consider non-emergent synchronized DC cardioversion for these patients after ensuring adequate sedation

The strongest data support procainamide for terminating Vtach, assuming the patient doesn’t have active ischemia or severe heart failure

For procainamide, remember, if the dysrhythmia stops, stop the procainamide. Other reasons to stop include hypotension, QRS prolongation over 50% of the original duration, a total of 1 g given, or acceleration of the tachycardia

Reflect to earn CME with Learner+

Sample reflection: I reviewed and reflected on the management of hemodynamically stable ventricular tachycardia, with a review of the evidence for pharmacological therapies and cardioversion.

This has been a guest post by Lloyd Tannenbaum, MD. Visit his Substack at:

Thank you for this. Keep ‘em coming

G-d gave us electricity b/c she wants us to use it.