Guideline Update on Difficult Airways

Extra prep for "physiologically difficult" airways is the new standard

Not long ago, patients frequently crashing before, during, or soon after intubation in the ED and ICU was considered an unfortunate but inevitable phenomenon owing to their severe illness.

It’s increasingly recognized that many of these dangerous and stressful situations are avoidable through the clear-eyed identification of high-risk patients followed by careful preparation and execution of the intubation procedure.

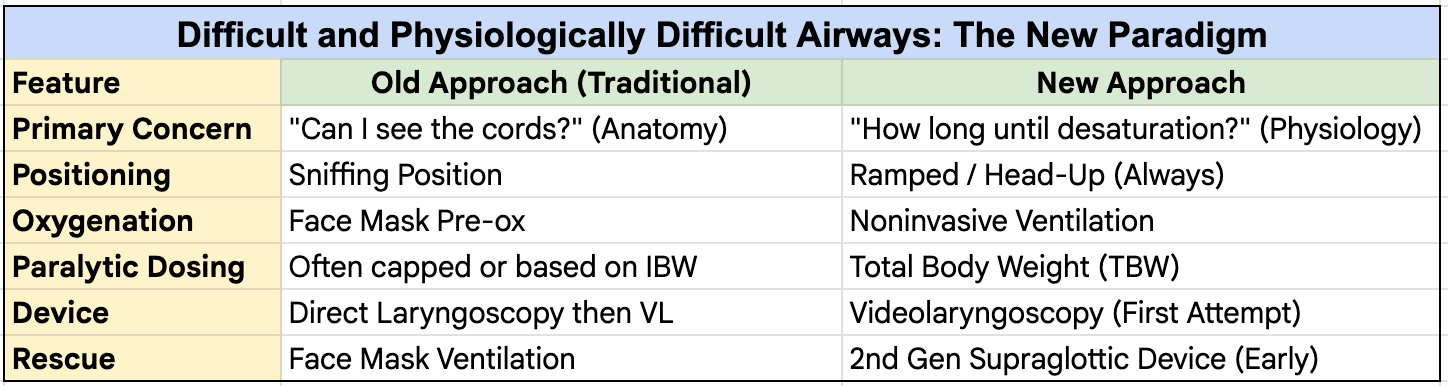

This is exemplified by the shift from a focus primarily on anatomically difficult airways, requiring an intense focus on technical considerations, to a more inclusive view of physiologically difficult airways, meaning patients who are more likely to become unstable (or moreso) during or after intubation.

The Difficult Airway Society is a multidisciplinary professional society focused on airway management based in the UK.

They released a 2025 update of their guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult tracheal intubation in adults.

Here are some of the highlights.

Most ED/ICU airways are “Physiologically Difficult”

Patients requiring intubation in the ED and ICU can usually be categorized as physiologically difficult, with hypoxemia, shock, severe metabolic acidosis, preload-dependent right heart failure, or a combination.

The guidelines also add a new focus on obese patients—more than 40% of people in the U.S. and 16% in Europe—as potentially difficult airways deserving of increased caution and preparation.

Obesity reduces functional residual capacity, the reservoir that is filled during preoxygenation; this can lead to rapid desaturation during induction.

Following the safety-oriented ethos of the new guidelines, the difficult airway cart/box/bag should probably be in the room more often—or better yet, the regular airway cart should be stocked with everything needed for difficult airways.

Plan for Success, Not Failure

The new guidelines are oriented toward maximizing first-pass success, not just managing the failed airway. This may seem like a subtle distinction, but it puts the emphasis where it should always be: reducing the possibility of complications before they occur.

Have a Plan A, B, C, and D

While planning for success, for every potentially difficult airway, there still needs to be a plan in the event things don’t go smoothly.

Tracheal intubation is plan A.

When that fails, facemask ventilation (e.g., Ambu bag) has been the traditional plan B. But second-generation supraglottic devices (e.g., iGel) are more effective and secure and are now recommended in the guidelines as the best plan B when intubation has been unsuccessful after a maximum of three attempts.

Facemask ventilation is advised as plan C, and emergency front-of-neck surgery (cricothyrotomy, such as with the scalpel-bougie-tube technique) plan D.

Everything for all these maneuvers should be in the room before starting the intubation.

If any difficulty with any of plans A - D is anticipated, awake intubation should be considered.

Videolaryngoscopy (VL) as First-Line

Videolaryngoscopy is recommended as the standard first-line method for intubation of potentially difficult airways. The evidence for VL over direct laryngoscopy for uncomplicated airways is persuasive; the evidence for video in increasing intubation success for difficult airways is even moreso.

Preoxygenate Head-Up at 30° with Noninvasive Ventilation (and NC O2)

Positioning at 30 degrees improves functional residual capacity and diaphragmatic efficiency. Patients can be kept in this position throughout preoxygenation and induction for optimal expected results.

Use of noninvasive ventilation during preoxygenation appears to prevent desaturation, as shown in the PREOXI trial.

By setting NIV in an “ST” or SIMV-equivalent mode that can deliver mandatory breaths, ventilation and oxygenation can be continued during induction (removing the mask and positioning flat immediately before intubation).

NIV (BiPAP) for preoxygenation before intubation prevented hypoxemia and cardiac arrest (PREOXI trial)

A large randomized controlled trial found significant reductions in hypoxemia and cardiac arrest among critically ill patients undergoing rapid sequence intubation who received noninvasive ventilation during the preoxygenation and apneic phases of RSI.

High-flow cannula oxygen (50-70L/min) or standard nasal cannula oxygen at high flow rates (15L/min) can also be applied to provide additional oxygen during the apneic period and intubation.

In critical care settings, conventional nasal cannula is more practical than HFNC (which interferes with the NIV mask seal) for this purpose, but a well-practiced team could easily swap NIV for HFNC at the time of intubation for high-risk patients.

Don’t Avoid or Underdose Neuromuscular Blockade

Neuromuscular blockade improves first-pass success and should be used routinely for RSI. If there is enough concern about a difficult airway not to use paralytics, awake intubation may need to be considered.

The package insert dosing for rocuronium is 0.6 to 1.2 mg/kg, but the guidelines suggest using the maximum of 1.2 mg/kg. This should be dosed for total (actual) body weight, not ideal body weight.

That’s 84 mg rocuronium for a 70 kg person, and 120 mg for a 100 kg person. (Other agents are appropriate, and their maximum doses should be considered as well.)

Plan for Hemodynamic Instability

In the RSI trial, 22% of ketamine-induced patients and 17% of those induced with etomidate had cardiovascular collapse (systolic blood pressure below 65 mmHg, new or increased dose of vasopressors, or cardiac arrest).

Fluid resuscitation and vasopressor infusion may be advantageous either before intubation or available for immediate use (i.e., already hanging on the IV pole).

Etomidate vs. ketamine for intubation induction (RSI Trial)

Etomidate and ketamine are the most commonly used agents to induce anesthesia before endotracheal intubation. Although etomidate is superior at quickly rendering patients unconscious, it suppresses adrenal function and has been suspected of causing more hypotension after intubation, relative to ketamine.

Here’s a Table of All That

Conclusion

By shifting from a reactive to a proactive mindset, it’s likely that many complications from endotracheal intubation in critically ill patients are preventable.

A rigorous and systematic approach to preoxygenation and prevention of hemodynamic collapse, applied to every “physiologically difficult” airway (i.e., most ED and ICU patients), and appropriate caution with obese patients, seems likely to prevent a large proportion of severe hypoxemia and hypotension.

It will have the additional benefit of making everyone else’s day less stressful, too.

Reference

Ahmad I, El-Boghdadly K, Iliff H, et al. Difficult Airway Society 2025 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult tracheal intubation in adults. British Journal of Anaesthesia. Published online November 2025. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2025.10.006