Transfusion in acute MI: what's the right hemoglobin target?

New meta-analysis with three smaller trials adds heft to MINT

A restrictive approach to red blood cell transfusion (e.g., transfusion to Hb ≥7-8 g/dL) is recommended in most critically ill patients after a mortality benefit was noted in the 1999 TRIC trial.

Should patients with acute myocardial infarction, or cardiac disease generally, be transfused to the same hemoglobin targets as other critically ill patients?

One-fifth of patients in TRIC had significant cardiac disease in the TRIC trial; they had no obvious increase in risk with a restrictive strategy, with numerically lower mortality of 20% versus 23% in the restrictive arm.

However, large observational cohorts have associated greater degrees of anemia with worse outcomes in patients with cardiac disease.

Three small-to-moderate-sized randomized trials diverged widely on whether a restrictive approach was safe (or even superior) in patients with MI.

The MINT trial then tripled the evidence base and provided persuasive, if not conclusive evidence that liberally transfusing patients with MI is beneficial.

In MINT, 3,504 patients with acute myocardial infarction and anemia were randomized to either a transfusion threshold of ≤8 g/dL, or a liberal transfusion threshold of ≤10 g/dL. After 30 days of follow-up, the composite outcome of all-cause mortality or myocardial infarction had occurred in 16.9% of the patients in the restrictive arm compared to 14.5% of patients in the liberal arm, with a relative risk of 1.15 (confidence interval 0.99 to 1.34, P=0.07).

A new meta-analysis combines the data from the three prior trials testing transfusion thresholds in MI with that of MINT. Here is a summary of the four trials:

Carson et al (investigators of MINT and its pilot) then performed a patient-level meta-analysis (NEJM Evid 2024) of all four trials.

With the additional ~820 patients added to the analysis, they concluded that a liberal transfusion strategy was non-significantly favored for:

Death at 30 days or myocardial infarction: 15.4% restrictive vs 13.8% liberal (relative risk [RR] 1.13, 95% confidence interval 0.97 to 1.30)

Death at 30 days: 9.3% restrictive vs 8.1% liberal (RR 1.15, 95% CI, 0.95 to 1.39)

Cardiac death at 30 days: 5.5% restrictive vs 3.7% liberal (RR 1.47, 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.94)

All-cause mortality at 6 months significantly favored the liberal transfusion strategy: 20.5% in the restrictive group and 19.1% in the liberal group (hazard ratio 1.08, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.11).

The Trees and the Forest (Plot)

That all looks pretty convincing. None of those far weaker studies dragged down MINT’s strong trend toward a benefit of liberal transfusion.

But that’s partly because the authors decided to use a fixed-effects model when comparing the four studies.

A fixed-effect model is generally for when there is believed to be one “true” effect of the intervention across all populations, and/or there is low heterogeneity of the populations studied. Usually, heterogeneity is assumed and a random-effects model is used for most meta-analyses.

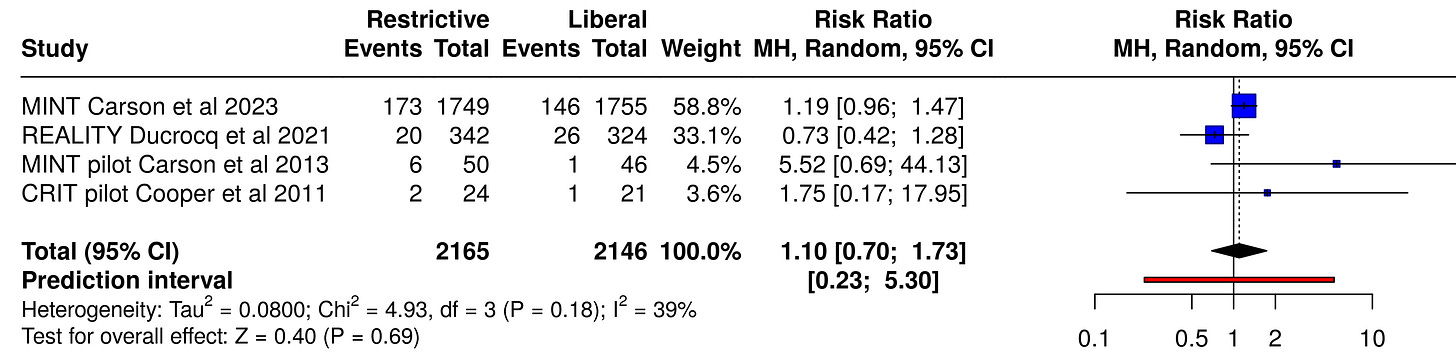

When we run the same reported numbers through a conventional meta-analysis calculator using the random effects method (which accounts for the expected heterogeneity between studies), we get a smaller effect size for 30-day mortality, with a relative risk of 1.10 and a much wider confidence interval of 0.70 to 1.73:

And for the composite outcome of death or MI, the primary outcome of the meta-analysis, again we find an even smaller effect size with a restrictive approach (a RR of only 1.08), with a much wider confidence interval (0.84 to 1.39 rather than 0.97 to 1.30), i.e., less certainty in the direction of the finding:

Fixed-effect models weigh the largest studies more heavily (owing to their lower standard error and internal variance). In the NEJM Evidence meta-analysis, that led to a weight of 85% for MINT, 15% for REALITY, and the other two studies each contributing 0.6% respectively (compared to 71%, 21%, 7% and 2% respectively for the random effects model).

Fixed-effect models are sometimes preferred when analyzing a smaller tranche of trials, to intentionally favor the largest, best-conducted studies. Here, one could argue that “including” two studies at a 1.2% combined weight made the meta-analysis look more inclusive than it is.

Conclusions

Combining the three smaller previous randomized trials with the much larger MINT trial in a patient-level meta-analysis did not demonstrate clear superiority of a liberal transfusion strategy to a hemoglobin of ≥10 g/dL in acute myocardial infarction, compared to a restrictive strategy to a target of ≥8 g/dL.

The dilution of MINT’s data with equivocal smaller trials did not significantly change the direction or precision of its findings, which favored a benefit of liberal transfusion (or risks of restrictive transfusion). The chosen statistical method helped ensure that.

Recent clinical guidelines have not advised specific transfusion targets in MI:

The observed strong trend toward clinical benefit seen in MINT with a liberal transfusion strategy will likely persuade many clinicians to transfuse patients with acute myocardial infarction to higher hemoglobin levels (e.g., ≥10 g/dL) rather than lower targets.

This is great. Will definitely keep this in mind when I take care of a patient with an acute MI.