Can driving pressure-guided ventilation improve outcomes? (REVIEW)

Largest-ever DESIGNATION trial enrolls abdominal surgery patients (not ARDS)

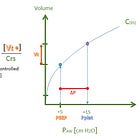

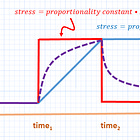

Driving pressure (ΔP), or plateau pressure minus PEEP ( ΔP=Pplat−PEEP ), is a variable pulmonologists love to obsess over. That’s partly because it’s useful, but also because it provides for impressively baffling speeches standing in front of the ventilator. The classic formula is

This is in the “pure,” passive ventilated patient without any dyssynchrony or auto-PEEP.

What they might not tell you is they’re really thinking about lung compliance, not pressures. The driving pressure is the cm of H2O it takes to inflate the lung and chest wall to plateau pressure from a specific PEEP. Yes, it’s expressed in units of pressure, but at any given tidal volume, a lower driving pressure equals higher compliance of the respiratory system (Crs). The real point of measuring the driving pressure is to measure compliance.

The above equation can be rearranged to make that clearer.

Higher compliance is good (for lungs, at least). Or if you prefer, a low elastance (Ers), which is compliance’s exact reciprocal and expresses the same relationship as a concept of stiffness (high=bad) rather than the spongy flexibility of compliance (high=good).

Higher driving pressures (at a given tidal volume) imply stiffer lungs. Lower driving pressures imply higher compliance. (Crs and Ers measure the whole respiratory system, including the chest wall, though; this becomes more salient during increased chest wall resistance, such as in obese patients; see below.)

The confusing part that keeps academic pulmonologists in business is that it is possible (and possibly desirable) for some mechanically ventilated patients to have slightly higher peak and plateau pressures, which sounds bad, simultaneously with lower driving pressures (which equate to higher compliance), which is good, as compared to another hypothetical patient being ventilated differently.

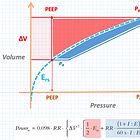

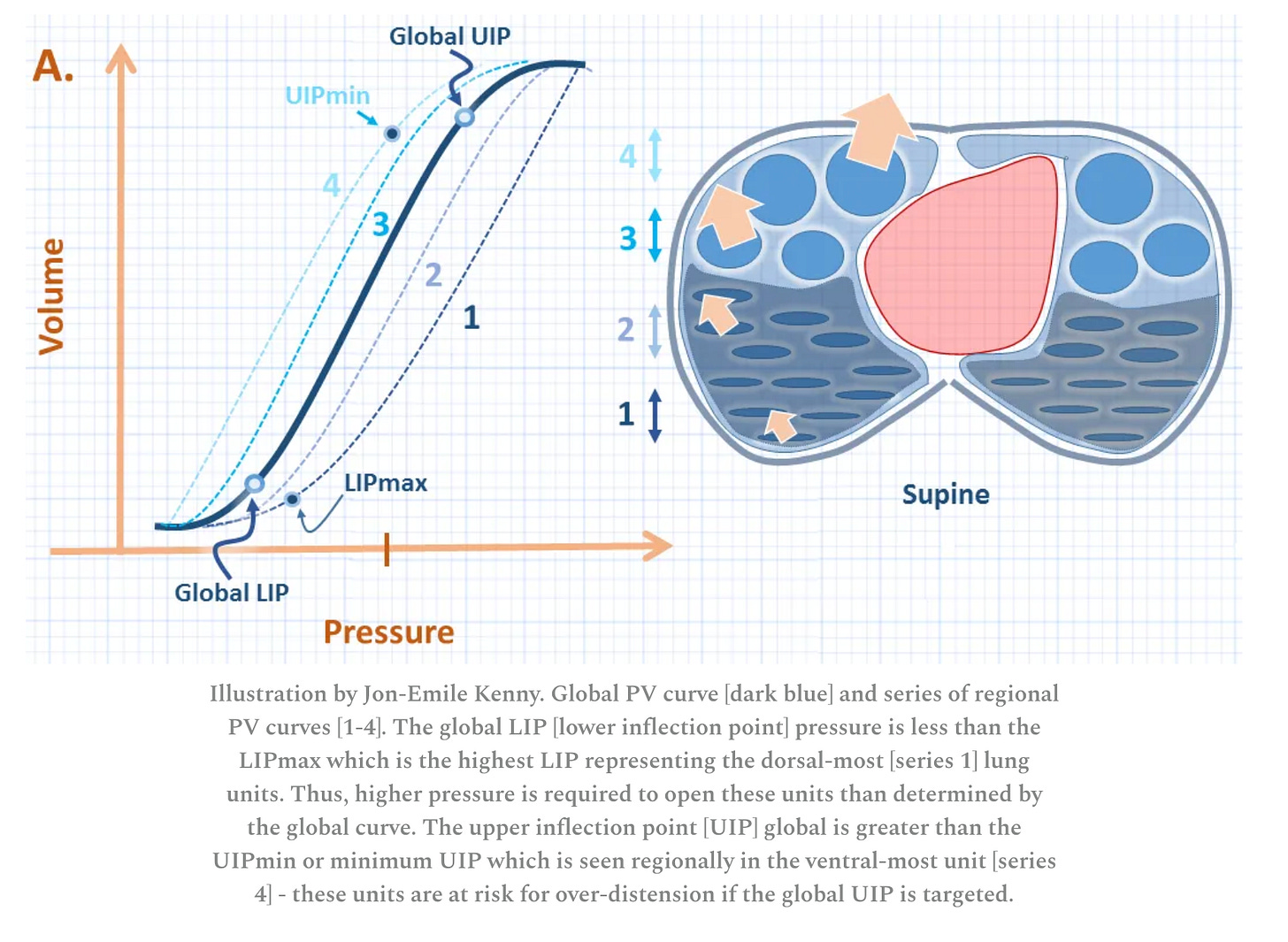

The key variable influencing all this is PEEP. Physiologically, when PEEP is too low, compliance decreases, as some of the initial pressure is spent popping alveoli open. (As a separate matter, excessive shearing forces from the repeated opening and collapsing of alveoli are also believed to cause ventilator-induced injury in ARDS patients.) When PEEP is too high, compliance also goes down due to alveolar overdistension.

Algebraically speaking, increasing PEEP always lowers driving pressure (improving compliance), as long as the resulting plateau pressure increase is less than the increase in PEEP.

These concepts are all explained even more confusingly here:

PEEP Titration to Optimize Driving Pressure

Driving pressure (ΔP) is an attractive surrogate for compliance because it can be relatively easily measured at the bedside (again, it’s plateau pressure minus PEEP).

By setting a tidal volume (e.g., 6 mL/kg) and then titrating up PEEP from 5 cm H2O, one can theoretically find the “Goldilocks” point at which PEEP is high enough to maintain an open lung without overdistension, while driving pressure is minimized.

PEEP titration will usually slightly increase plateau pressure, but the beneficial reduction in driving pressure is thought to be a worthwhile trade, as long as plateau pressure stays in a safe range (goal ≤30 cmH2O in ARDS).

There is no magic number for a “good” driving pressure, but ≤15 cmH2O is commonly thrown around as favorable (e.g., plateau 20 / PEEP 5 or plateau 25 / PEEP 10; etc).

Ever since lower driving pressures were observationally linked to improved mortality in ARDS, researchers have been testing PEEP titration to optimize driving pressure in mechanically ventilated patients.

Thus far, the project hasn’t turned up anything that could be called practice-changing.

Driving Pressure Targeted Ventilation in Abdominal Surgical Patients (DESIGNATION Trial JAMA 2025)

Since 50 million people undergo abdominal surgery each year, a small reduction in postoperative pulmonary complications would go a long way.

Among 1,435 adults undergoing open abdominal surgery at multiple centers across Europe, investigators incrementally titrated PEEP up to 20 cmH2O and then decrementally back down to 6, plotted the pressures observed, then selected the PEEP producing the lowest driving pressure (in half the randomized patients; the other half were kept at PEEP 5 cmH2O).

The strategy was technically successful: the high PEEP group had lower driving pressures. However, there were no differences in pulmonary complications (numerically higher in the high PEEP group, not significant).

Patients in the high PEEP group had more hypotension and required more vasopressors during their surgery, though, while the lower PEEP patients had more episodes of oxygen desaturation.

The STAMINA Trial (Br J Anesth 2025)

In STAMINA, PEEP was likewise individually titrated for each patient to optimize their compliance. Once their optimal PEEP was set, their tidal volumes were reduced to reduce driving pressure to the lowest level that could support adequate gas exchange.

For control arm patients, PEEP was titrated according to a low PEEP:FiO2 ARDS table (e.g., PEEP 5 for FiO2 30%, up to PEEP 18-24 for FiO2 100%). Plateau pressure ≤30 cm H2O was targeted for all patients.

Target enrollment was 500, but STAMINA was stopped early from “recruitment fatigue” after 214 patients were enrolled.

Among the 198 available for analysis, there were no differences between groups in ventilator-free days (6 vs 7, P=0.28).

The underpowering produced an absence of evidence, rather than evidence of absence.

Meta-Analysis at Sichuan U (Crit Care 2025)

Only four RCTs (n=465) were available for this meta-analysis; the trials were conducted in Brazil, Colombia, Egypt, and Thailand.

Patients had ARDS and were randomized to a driving pressure limiting strategy or usual care (low-tidal volume or lung protective ventilation).

There were no significant differences in mortality (odds ratio 1.01), ICU mortality, in-hospital mortality, ventilator-free days, or length of hospital stay, nor in the incidence of pneumothorax. A reduced ICU length of stay was observed in the pooled driving-pressure arms.

Obesity Increases Driving Pressure (Benignly?)

Obesity complicates the driving pressure relationship. Obese patients have increased chest wall stiffness (higher elastance, lower compliance). At a given tidal volume, an obese patient will tend to have higher plateau pressures and driving pressures than a normal-weight patient. The delta in driving pressure is “spent” distending the chest wall. This occurs without any change in lung mechanics.

This can spuriously make it appear as if obese patients are experiencing more lung stress than they are.

Esophageal manometry can be used to more closely approximate the plateau pressure and end-expiratory pressures in the airways, without the chest wall’s contribution.

This engages the concept of transpulmonary pressure (the isolation of “lung stress” from the greater respiratory system) and adds another layer of complexity to the aforementioned equations, but the net result (as most clinicians are aware) is that more PEEP may be needed to prevent alveolar collapse.

Conclusions

Driving pressure is a surrogate for the inverse of respiratory system compliance (lower ΔP = higher compliance = lower elastance), which can be useful in adjusting mechanical ventilation settings and confusing non-pulmonologists.

PEEP can be titrated up to (theoretically) optimize driving pressure to the lowest level at the highest PEEP. Thus far, ventilation strategies based on this scheme have not shown improved outcomes.

The only large trial (DESIGNATION) was conducted in abdominal surgery patients with a low risk of bad outcomes; it did not find a reduction in postoperative pulmonary complications. Patients with severe lung injury would be theoretically most expected to benefit from a driving pressure-limiting strategy, but this has not yet been tested in a large RCT in ARDS patients.

References

Aarts LPHJ, Aarts F, Akkerman RDL, et al. Intraoperative Driving Pressure–Guided High PEEP vs Standard Low PEEP for Postoperative Pulmonary Complications. JAMA. Published online December 3, 2025. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2025.23373

Amato MBP, Meade MO, Slutsky AS, et al. Driving Pressure and Survival in the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(8):747-755. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa1410639

Cheng J, Ma A, Liang G. Driving pressure-limited ventilation strategies versus conventional lung protective ventilation strategies for patients with ARDS/ARF: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Critical Care. 2025;29(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-025-05722-y

I find it a bit curious to take an observed post hoc phenomenon from ARDS trials where only a tiny minority of the interventions tried over a 30 year period were efficacious despite a disease with a mortality of 25%, and then try to apply it to a group of patients undergoing abdominal surgery which should have a very low mortality and should not have the substrate disease upon which the therapy might be beneficial (lung injury) and in which the observed driving pressure phenomenon was documented, all the while looking for end points such as mortality which are unrealistic, or “pulmonary complications” that have too high of variance